Three Days, Two Snowstorms

Joe Munchak is a scientist at Goddard Space Flight Center who specializes in remote sensing of snow. This week he is at the CARE site in Ontario as one of the operations scientists for the GCPEx ground validation.

It’s been a relatively eventful few days here in Barrie, Ontario, with two coordinated air-ground campaigns over the past three days. I was actually driving to Barrie from my home in Maryland during the first event (January 28th), and got to experience some lake effect snow bands first-hand in northern Pennsylvania on my way up. These were very narrow, only a few miles wide, but heavy enough to drop an inch or two during the 15 minutes or so I encountered them! Fortunately, temperatures were just above freezing so roads stayed mostly wet, although there were some icy sections at higher elevations.

That event can be contrasted with the longer duration, but weaker intensity synoptic-scale event we experienced yesterday (January 30th). A synoptic event is a few hundred miles wide, and is driven by large-scale warm and cold fronts – in yesterday’s case, it was a warm front. Because they are larger, synoptic events can be anticipated by forecasters a few days ahead, and this was no exception. We had a pretty good idea by Sunday morning that Monday evening would present a great opportunity for observations, so we began to prepare.

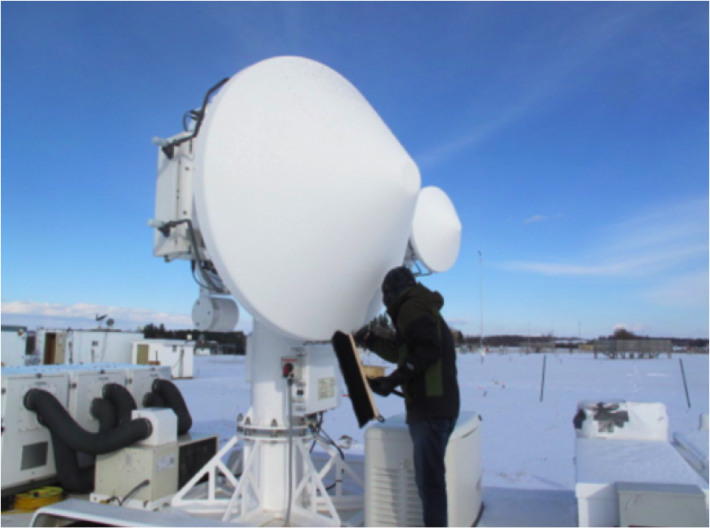

Preparation for an event involves alerting the flight crews of both of the planes we’re using (the Citation and DC-8) so they can adjust their schedules, and ensuring that the instruments are ready to go. One of the many instruments we have on the ground is the D3R – that stands for Dual-polarized Dual-frequency Doppler radar. Saturday’s wet snowfall left a thin crust of ice on the antenna, which isn’t good because it weakens the radar beam, not allowing us to see as far into the storm as usual. In order to fix this Vijay, our radar engineer, set the radar to move so that it stayed facing the Sun to melt some of the snow off. Then, he chipped and swept off what was left with a broom and snow shovel.

Monday morning we had a final forecast discussion led by Eyad Atallah from McGill University. At this point we had confidence that it was going to snow, but we needed to know the 3-hour window of the heaviest rates because the Citation only has enough fuel for 3 hours of observations (the DC-8 can go a little longer, about 5 hours). Pinpointing this type of timing can be hard even 12 hours out, and is part of the reason we have dedicated forecasters for this project. We ended up deciding on a 7PM-10PM window as the most likely time for the heaviest snow.

After a leisurely mid-day, we arrived at our nerve center, the Center for Atmospheric Research Experiments (CARE). After confirming that the storm was on track in the warm, cozy confines of the CARE office building, we made our last minute instrument checks and began ground-based observations from a chilly, cramped trailer hooked up to dozens of ground instruments and aircraft communications. It didn’t take long for the trailer to warm up, as up to 8 scientists took their positions and monitored instruments and aircraft, trying to coordinate observations as much as possible. Nor did we have to wait long for the snow to begin, with the first flakes falling around 4 PM and gradually increasing from flurries to a steady, moderate snowfall within an hour’s time.

Was the forecast off? Would our aircraft observations miss the heaviest snow? We were able to scramble the Citation an hour early, and it began taking observations at 6 PM. The DC-8 joined right on schedule at 7PM just at the peak snowfall rate over the CARE site. We were able to get a full two hours of coordinated observations as about 2 inches (3cm) of snow fell. At the same time as the aircraft were flying overhead, we were constantly scanning with our ground radars and measuring snowfall rates and snowflake sizes and shapes with an armada of ground instruments.

Our preliminary look at the data seems to indicate that this was a good event, with all aircraft and ground instruments performing up to expectations. The exciting part for us as researchers comes in the months ahead as we try to form a consistent picture between the direct measurements of snowflakes on the ground and the aircraft observations, which are similar to the ones the GPM satellite will make from space.